Groundwater pumping has reduced U.S. stream flows

Groundwater pumping in the last century has contributed as much as 50 percent to stream flow declines in some U.S. rivers, according to new research by hydrologists at Colorado School of Mines and the University of Arizona.

Groundwater pumping in the last century has contributed as much as 50 percent to stream flow declines in some U.S. rivers, according to new research by hydrologists at Colorado School of Mines and the University of Arizona.

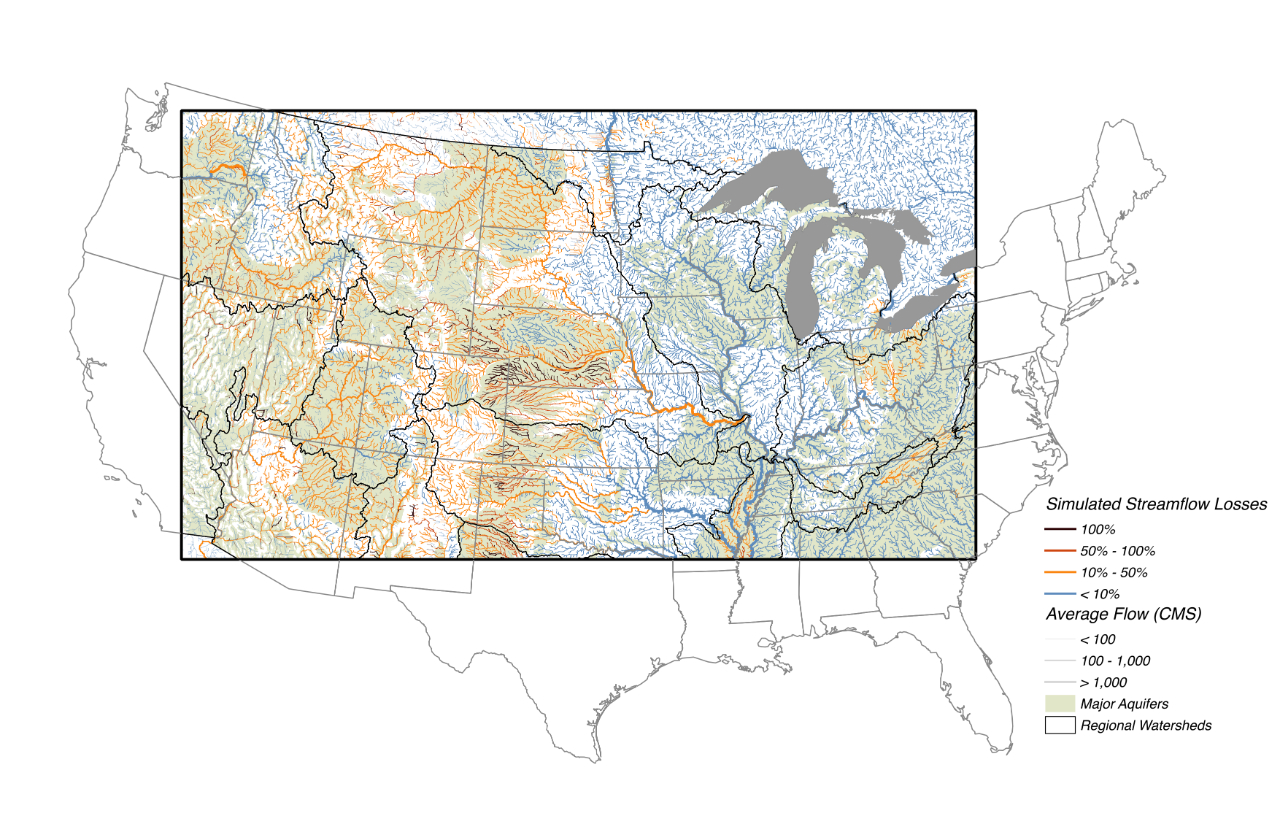

Streams, lakes and rivers in western Nebraska, western Kansas, eastern Colorado and other parts of the High Plains have been particularly hard hit by groundwater pumping, the scientists found.

“This study has important water rights implications,” said Reed Maxwell, Rowlinson professor of hydrology at Colorado School of Mines and co-author of the new paper. “The state of Colorado, for one, has to deliver a certain amount of water to downstream states and groundwater pumping may inadvertently be affecting our ability to do that.”

Laws regulating the use of groundwater and surface waters differ from state to state. Some Western states, Arizona among them, manage groundwater and surface water separately.

This is the first study to look at the impact of past groundwater pumping across the entire U.S. Other researchers have examined how groundwater pumping affected surface waters, but at smaller scales.

“We showed that because we’ve taken all of this water out of the subsurface, that has had really big impacts on how our land surface hydrology behaves,” said lead author Laura Condon, a UA assistant professor of hydrology and atmospheric sciences. “We can show in our simulation that by taking out this groundwater, we have dried up lots of small streams across the U.S. because those streams would have been fed by groundwater discharge.”

Using a computer model, Condon and Maxwell determined what U.S. surface waters would have been like without significant consumptive uses and compared that with surface water changes since large-scale groundwater pumping began in the 1950s.

The scientists focused primarily on the Colorado and Mississippi River basins and looked exclusively at the effects of past groundwater pumping because those losses have already occurred.

The U.S. Geological Survey has calculated the loss of groundwater over the 20th century as 800 km3, or 649 million acre-feet. That amount of water would cover the states of Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico plus most of California with water one foot deep.

“We can do things with these model simulations that we can't do in real life. “We can ask, ‘What if we never pumped at all? What's the difference?’” Maxwell said. “With this study, we not only have been able to reconstruct the impact of historical pumping on stream depletion, but we can also use it in a predictive sense, to help sustainably manage groundwater pumping moving forward.”

The regions most sensitive to a lowering of the water table are east of the Rocky Mountains, where initially the water table was shallow, at the depth of six to 33 feet (two to 10 meters). In those regions, groundwater and surface water are more closely linked and depleting the groundwater is more disruptive to vegetation and to streams and rivers.

In the western U.S., the groundwater was already deep, so reducing the groundwater didn’t have as great an effect on surface waters.

Other research has shown that parts of the U.S. Midwest where the precipitation used to equal the evaporative demand – meaning plants didn’t need irrigation – are becoming more arid, Condon said. Those are some of the regions where groundwater pumping has reduced surface waters.

Groundwater helps provide water to existing vegetation, including crops. Receding water tables and dwindling streams can make irrigating crops more difficult and costly. Some native vegetation including cottonwood trees will eventually die if the water table drops below their roots. Groundwater is often the slowest component of the terrestrial hydrologic system to recover from losses.

Condon and Maxwell’s article, “Simulating the sensitivity of evapotranspiration and streamflow to large-scale groundwater depletion” was published in the journal Science Advances on June 19. The U.S. Department of Energy funded the research.

CONTACT

Emilie Rusch, Public Information Specialist, Colorado School of Mines | 303-273-3361 | erusch@mines.edu

Mari N. Jensen, Public Information Officer, College of Science, University of Arizona | 520-626-9635 | mnjensen@email.arizona.edu