An autonomous AED-delivering robot? These Mines students developed one in 36 hours and won SB Hacks.

Mines seniors, from left, Van Wagner, Parker Steen, Peter Wilson and Joshua Rands won the grand prize at SB Hacks at the Univeristy of California, Santa Barbara, for their Fully Autonomous AED Emergency Response System.

Automated external defibrillators increase survival rates from sudden cardiac arrest, but only 50 percent of people know where to find an AED unit at work, according to the American Heart Association.

Seconds count when it comes to the potentially life-saving intervention, too – for each minute that passes without CPR and defibrillation, the chance of survival decreases 7 to 10 percent.

“AEDs are only used 20 percent of the time, but they more than double your chance of survival,” said Parker Steen, a senior majoring in mechanical engineering. “They’re vital for cardiac arrest incidents. You don’t have a lot of time to find one.”

To devise a solution to that challenge, Steen and a team of fellow mechanical engineering and computer science students from Colorado School of Mines recently put their programming and robotics skills to the test – and in doing so, were named the winners of SB Hacks VI, held at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

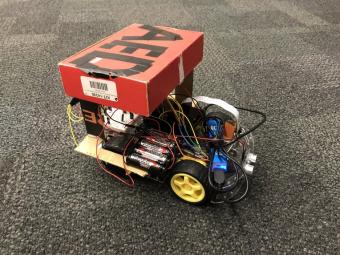

Over the course of the 36-hour hackathon, the Mines team designed and built the Fully Autonomous AED Emergency Response System, which used security camera footage to automatically detect if someone in the building is suffering from sudden cardiac arrest and then dispatched a robot carrying an AED to that location.

“The original idea was to have some sort of buttons on the wall that you could use to call the AED,” said Van Wagner, a senior majoring in mechanical engineering. “After talking about it some more, we decided to build on that and try to do something even bolder and make a computer vision algorithm that would use security cameras to identify when someone has a heart attack.”

“We built and trained our own neural network in one weekend. That’s pretty crazy – in order to train a neural network, you need thousands and thousands of data points,” said Josh Rands, a senior majoring in computer science. “We did it by taking videos of ourselves walking around behaving normally and then faking a heart attack. We split those videos in frames and labeled every individual frame ‘heart attack’ or ‘no heart attack.’”

Not that everything went smoothly during the programming marathon.

After getting lucky with their first stab at the neural network, the team ended up having to train six separate networks to get one that worked consistently, Rands said.

“The first one worked for Parker as the test subject every single time but only for Parker and the camera had to have the same background,” Rands said. “It was a cool learning experience to have to build something more robust, but it took a lot of time and a lot of videos.”

The team also had to pivot when their original plan to use Bluetooth for figuring out where the robot was didn’t pan out, Wagner said. Instead, they integrated break beam sensors for localization and used a computer vision library for object detection, with teammate and mechanical engineering senior Peter Wilson taking the lead on building the controller.

“Basically, the robot could scan over the room and find where the person lying down on the ground was, and Pete built a controller that would keep that person in frame as the robot worked its way over there,” Wagner said. “It was able to have each room hard-coded in, make its way to each room and then once it’s there, it was actually fully autonomous and depending on the situation could find any person.”

The team is no stranger to the sleep-deprived, caffeine-fueled environment of hackathons. Last year, they won the MakeHarvard Originals Award for a project that also showed off both their hardware and software skills, a brain-controlled wheelchair built and designed solely with materials provided at the event.

"It’s really satisfying to see what you can accomplish if you sit down and set your mind to something for 24 or 36 hours – a group of four people working toward a common goal, it’s pretty impressive what you can complete just given that short amount of time,” Wilson said.

This time around, that included teaching themselves machine learning in a matter of hours.

“None of us had done machine learning before – to get the chance to sit down for 20 hours straight and figure out how it works, now that’s a skill we can say we have,’’ Rands said. “You don’t really have time as a full-time student to pick up skills like that outside of class, except at an event like this.”