Mines PFAS expert weighs in on regulating "forever chemicals"

Group of experts across PFAS-related sectors considers various regulation options for “forever chemicals”

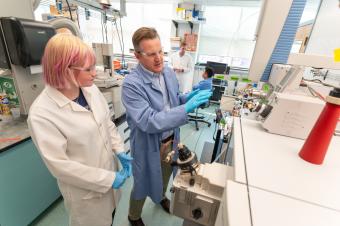

Chris Higgins, University Distinguished Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Colorado School of Mines, is among an international group of environmental consultants, regulators, land managers and academics that have jointly published an evaluation of differing approaches to regulation of the substances popularly known as ‘forever chemicals.’

The recommendations, published this week in the journal Remediation, focus on the challenges associated with two ends of the regulatory spectrum for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): regulation as a single class of chemicals (all PFASs) or regulation on a chemical-by-chemical basis.

“Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, often called ‘forever chemicals’ because they have a very long lifetime in the environment, are increasingly being detected in people and the environment and the U.S. EPA just finalized drinking water regulations for six of these compounds,” Higgins said. "But despite the appeal of a simple means to regulate all compounds containing organic fluorine the same way, our professional opinion is it simply isn't technically feasible. There are multiple reasons beyond the technical - such as ensuring the polluter pays - that a whole-class approach is problematic for contaminated water and soil."

The international effort was led by Karl C. Bowles, Senior Principal Environmental Scientist at Jacobs. Co-authors represent a wide range of experts on PFAS fate and transport, remediation, regulation, and toxicology, hailing from industry, government and academia in Australia, Canada, Sweden, the U.S. and the UK.

Regulation of PFAS is complicated, the authors agree, by the fact that this broad group of compounds has a range of different physical, chemical, and toxicological properties.

The authors point out that not all PFASs pose the same risks to human health or the environment, and regulating PFASs as a single class may mean over-regulating in many cases. Regulating as a single class may also result in environmental liability for detected PFAS that are unrelated to the responsible party’s release – for example, low-level anthropogenic background sources – challenging the principle of “polluter pays.”

Additionally, current analytical tools are not standardized to identify all PFASs, and remediation strategies vary in effectiveness across different varieties of PFASs.

Regulating on a chemical-by-chemical basis presents a different set of challenges. Specifically, with the vast number of different PFASs (which vary based on how a PFAS is defined – also a subject of much debate), the authors acknowledge that analytical tools and methods to generate data for each chemical do not presently exist. Therefore, understanding the critical toxicity and exposure characteristics for each individual PFAS is not feasible and would lead to uncertainty in both regulation and mitigation efforts.

A third alternative option is posed by the authors, namely regulating PFASs based on subgroups that are based on chemical structural properties and aligned to hazard categories. This approach has established precedent having already been used to regulate sites contaminated with hydrocarbons.

“This effort, to get experts with extensive experience in researching and managing PFAS contamination together to provide insight and guidance on PFAS regulation, is extremely timely, given the recent U.S. EPA announcement,” Higgins said. “To protect human health and the environment, we need to develop the right strategies around regulating PFASs.”

To read the full piece, “Implications of grouping per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances for contaminated site regulation,” go to http://doi.org/10.1002/rem.21783.