Colorado School of Mines students received an insider’s view of the brewing crisis between the United States and North Korea when they video-conferenced with an American scholar who just returned from the Korean peninsula.

Professor Mitchell Lerner, who directs the Institute for Korean Studies at Ohio State University, toured the demilitarized zone along the border between North and South Korea last week and met with government officials to discuss the rising tensions over Pyongyang’s ballistic missile and nuclear weapons programs.

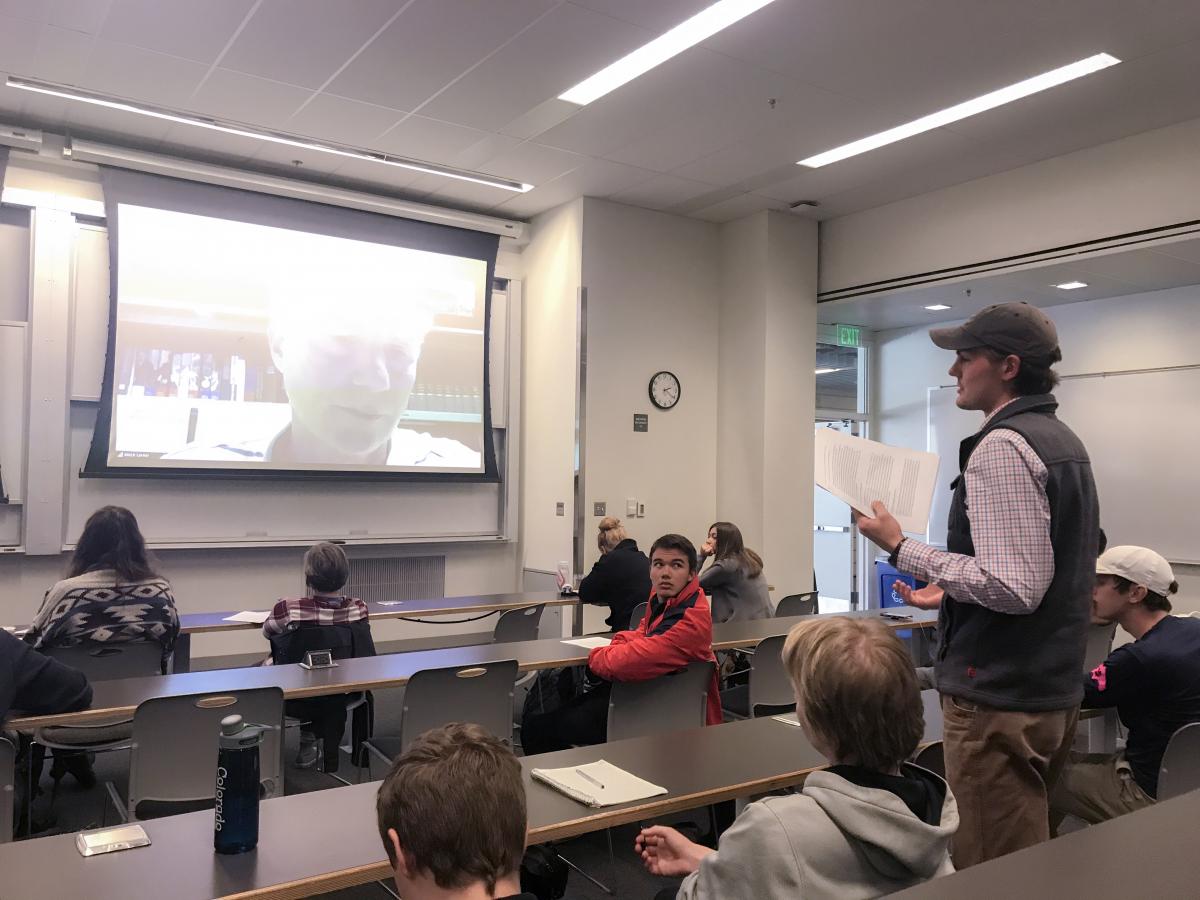

Lerner, whose face was projected live on two large screens in Marquez Hall, fielded questions from the class of 70 students in a humanities course studying the origins of several global crises, including that in Korea. His message took students by surprise.

Lerner, whose face was projected live on two large screens in Marquez Hall, fielded questions from the class of 70 students in a humanities course studying the origins of several global crises, including that in Korea. His message took students by surprise.

Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump may be threatening “nuclear clouds” and “fire and fury,” but many in South Korea are really not that alarmed by North Korea’s nuclear program, Lerner reported, based on his many meetings in Seoul last week. “Remember that South Korea has lived with the threat of war for over six decades,” he told the students. There are over 15,000 pieces of artillery pointed at Seoul, plus rocket launchers and enormous stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons, including the VX nerve agent.

For South Korea, Lerner said, “the threat hasn’t changed that much.” What has them worried, he said, “is the uncertainty about how the U.S. will respond.”

In addition, many in South Korea are worried about the viability of the U.S. security guarantee. If North Korea develops the ability to strike the United States with nuclear weapons, will the U.S. honor its commitment to defend South Korea in the event of war? Lerner says he was asked this question repeatedly during his visit.

Lerner’s briefing on the current status of the Korean crisis was meant to prepare the Mines students for a simulated meeting of the National Security Council that took place in class later in the week. They are studying modern international relations using a learning tool called “Model Diplomacy,” prepared by the Council on Foreign Relations, an influential think tank based in Washington, D.C.

In the simulation, students in the class assume key policymaking roles, such as secretary of defense or secretary of state, which they must research in depth. Then they must advocate for a policy position in a mock NSC meeting, presided over by a guest playing the part of the president.

Students capitalized on Lerner’s experience to help them prepare for the simulation, asking him pointed questions about how the United States should respond to the crisis.

“Is there a military solution?” Not a good one, answered Lerner, pointing out that any strike against North Korea would trigger a massive attack on the south, leaving the country devastated, risking a wider war and wreaking havoc on the global economy.

“Can economic sanctions work?” asked one student. It is doubtful that more sanctions could do much good, Lerner said. North Korea has lived for decades under extreme deprivation. A famine in the 1990s killed two million people. North Koreans have learned to survive under the toughest conditions, and the regime has managed to remain total control over the population. Sanctions, Lerner said, were unlikely to change all this.

Another student sought clarification: “Is it realistic to expect China to put pressure on North Korea by reducing its trade?” China has much less influence over North Korea than most Americans think, Lerner cautioned. “North Korea has been a pain for everyone, including China and Russia.” American policymakers consistently exaggerate China’s ability to be part of the solution.

Students also asked questions about the thriving black market in North Korea, as well as the country’s class structure and system of government.

The simulated NSC meeting challenges students “to think on their feet,” says Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Professor Kenneth Osgood, the course instructor and a historian of U.S. foreign policy. “They also have to deal with complicated problems for which there’s no clear answer. They have to communicate clearly. And they have to negotiate with their peers to find a path forward.” Such skills, Osgood says, are critical for engineers and scientists, no less than history or political science majors.

To inject an element of authenticity, Osgood hosts the mock NSC meetings in a room dressed up to resemble a formal White House conference room. Surprise guests play the presidential role to keep students “on their toes,” Osgood says.

A Mines alum, Richard Sebastian-Coleman, was the first guest president when the class discussed Russian expansion in Ukraine and the Baltics. For the Korean simulation, the presidential role was played by Elizabeth Davis, a specialist on the Asia-Pacific region and a Mines faculty member from the Division of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences.

Osgood says he will not disclose who the other guest presidents will be. “I’m excited because we’ve got some great guests, including one big surprise, but I’m keeping their identities a secret.” he said. “Being a little nervous from the uncertainty is a good thing if it gets students on their game.”

Osgood will say, though, that he has additional briefings planned to help students prepare for their simulations. When the class examines the Iran nuclear deal, they will be briefed via videoconference by Mike Doran, who served in the George W. Bush administration. He was a senior director in the National Security Council, where he was responsible for helping to devise and coordinate United States strategies on a variety of Middle East issues, including U.S. efforts to contain Iran and Syria.

In addition, the course will include public discussions with the broader campus community about U.S. foreign policy and its history. Jason Parker, a prize-winning historian from Texas A&M, will speak on the impact of decolonization on U.S. foreign relations on October 23 at 6 p.m. in Brown W250. Later, Jeremi Suri, a frequent media commentator and leading scholar of U.S. foreign relations, will speak on his acclaimed new book The Impossible Presidency on November 17 at 2 p.m. in the Student Center. Both lectures, plus the guest experts in Osgood’s class, are made possible by funding from the Hennebach Program in the Humanities.

Mason Elliott, a sophomore petroleum engineering major, played the critical role of national security advisor during the simulated meeting to discuss the Korean crisis. He described Lerner’s briefing as “eye-opening” and “very helpful.”

But the briefing also came to a depressing conclusion.

“There’s no good answer about what to do about North Korea,” Lerner advised the class, as heads nodded in agreement.

“Give me a policy option, any option, and I will rip it apart because they are all bad. What we’re looking for is the least terrible solution.”

Contact:

Ken Osgood, Professor, Humanities, Arts & Social Sciences | 303-273-3870 | kosgood@mines.edu

Mark Ramirez, Managing Editor, Communications and Marketing | 303-273-3088 | ramirez@mines.edu